| |

Ancient DNA (aDNA) analysis

Ancient DNA (aDNA) analysis is a new

research tool with many applications in

fields ranging from genetics through

emerging diseases to forensic medicine. aDNA

techniques provide a unique opportunity to

retrieve genetic information about past

populations unavailable by any other

approach.

The long-term goal of the present research

is to establish a "stratigraphy of genetic

profiles" of the diverse populations which

inhabited Israel in the past, untangling

their inter-group relationships as well as

their genetic links to other cultures in the

Middle East and Europe.

Projects:

a) population origins and movements in the

Southern Levant;

b) origin and spread of genetic disorders in

past populations of the Mediterranean Basin;

Infectious diseases in the past

In ancient Europe, tuberculosis was one of

the most widely prevalent infectious

diseases. Incidence of bone pathology in

skeletal remains from medieval Lithuania

suggests that 18-25% of the population

suffered from the disease. We have detected

the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis

in skeletal remains from Lithuania, dated to

the 15th to 17th centuries by amplifying a

part of a repetitive insertion element-like

sequence (IS 6110). DNA of the bacillus has

been identified both in pathological and

normal tissues (bones and even teeth) of the

same individuals, proving hematogenous

spread of bacilli. Moreover, presence of M.

tuberculosis DNA has been demonstrated also

in skeletal remains of individuals without

specific lesions. The results indicate that

a much higher percentage of individuals were

infected than previously thought. Our

findings open the possibility of examining

the actual prevalence of tuberculosis in

ancient populations from collections in

which individuals are represented by single

bones or teeth.

Forensic and archaeological applications

Gender determination of skeletal remains has

considerable importance on forensic and

archaeological studies. However, the

accuracy of identification from morphometric

analyses is limited in the case of

fragmentary remains of adults, or even

complete remains of children. Blind studies

carried out on specimens of known gender,

have demonstrated that while correct

identification may reach as high as 90-95%

for complete adult skeletons, it may fall to

60% or less when dealing with fragmentary

remains or infant skeletons. New

developments in molecular biology have

provided alternative and reliable methods

for gender determination based on

identification of DNA sequences specific to

the X and/or Y chromosomes.

Gender and Burial customs

Today archaeologists are paying increasing

attention to examining social structure

within past societies. Archaeological

studies of gender differences especially in

regard to children have been traditionally

explored through identification of grave

goods considered indicative of female or

male roles. Physical anthropology expands

the study of mortuary practices through

direct identification of sex, even when

grave goods are absent. The reliability of

such analyses varies with the condition of

the bones. For a complete adult skeleton it

approximates 90-95%. However, in fragmentary

remains, or those of infants, the

reliability of sex identification falls as

low as 60%.

Recent developments in molecular biology in

analyzing DNA recovered from ancient bones

have provided reliable methods for gender

determination based on amplification of DNA

sequences specific to the X and/or Y

chromosome (Faerman et

al., 1995). Population structure,

male and female status in past societies,

and gender differences in burial practices

can now be attempted even on fragmentary

skeletal remains as well as those of infants

and children. In Israel, these infant

remains may have been treated with great

care, as for example, the jar burials with

grave goods found at Tel-Teo (Kahila

Bar-Gal & Smith 2001), or

alternately, with complete disregard, like

the infants thrown into sewers in Late Roman

Ashkelon (Smith &

Kahila, 1992).

Out of the 17 burials found at Tel Teo, the

Huleh valley, 10 were infants, with 6 of

them dated to the pottery Neolithic and the

remainder dated to the Chalcholithic and

Early Bronze Age. Nine of these were

subjected to DNA-based sex identification (Smith

et al, 1999). The results were

consistent with all five specimens (of

nine), which yielded amplifiable DNA, being

male.

This method was applied to clarify the

social basis of infanticide in Late Roman -

Early Byzantine Periods (Faerman

et al, 1997; 1998). Skeletal remains

of some 100 neonates were discovered in a

sewer, beneath a Roman bathhouse, which

might have also served as a brothel. Written

sources indicate that in ancient Roman

society infanticide was commonly practiced,

and that females were preferentially

discarded. DNA-based sex identification of

the 43 infant left femurs provided results

in 19 specimens (14 males and 5 females),

indicating that both male and female infants

were victims of infanticide in Ashkelon.

These findings suggested that the infants

might have been offspring of courtesans,

serving in the bathhouse, supporting its use

as a brothel. Later this research was

expanded to Roman Britain (Mays

& Faerman 2001).

Genetic history of modern Israeli

populations

We examined the genetic relationship among

three Jewish communities, the Ashkenazi,

Sephardic and Kurdish Jews, who were

geographically separated from each other for

many centuries. By comparison with Y

chromosome haplotypes of other Middle

Eastern populations we asked how the Y

chromosomes of Jews fit into the genetic

landscape of the region. A sample of 526 Y

chromosomes representing six Middle Eastern

populations (Ashkenazi, Sephardic and

Kurdish Jews from Israel, Moslem Kurds,

Moslem Arabs from Israel and the Palestinian

Authority Area, and Bedouins from the Negev)

was analyzed for 13 binary polymorphisms and

six microsatellite loci. The investigation

of the genetic relationship among three

Jewish communities revealed that Kurdish and

Sephardic Jews were indistinguishable from

each other, while both differed slightly,

yet significantly, from Ashkenazi Jews. The

differences in Ashkenazim may reflect

divergence due to genetic drift during

isolation and/or low-level gene flow from

European populations. Admixture between

Kurdish Jews and their former Moslem host

population in Kurdistan appeared to be

negligible. In comparison with data

available from other relevant populations in

the region, Jews were found to be more

closely related to groups from the north of

the Fertile Crescent (Kurds, Turks and

Armenians) than to their Arab neighbors. The

two haplogroups Eu 9 and Eu 10 constitute a

major part of the Middle Eastern Y

chromosome pool. Our data suggest that Eu 9

originated in Turkey and Eu 10 in the

southern part of the Fertile Crescent.

Genetic dating yielded estimates for the

expansion of these haplogroups that mark the

Neolithic/Chalcolithic Period in the region.

Palestinian Arabs and Bedouins differed from

the other Middle Eastern populations studied

here mainly in specific high-frequency Eu 10

haplotypes not found in non-Arab groups. We

postulate that these chromosomes were

introduced through migrations from the

Arabian Peninsula over the last two

millennia. This study contributes to the

elucidation of the complex demographic

history that shaped the present-day genetic

landscape in the region.

Nebel, A., Filon, D., Weiss, D., Weale, M.,

Faerman, M., Oppenheim, A., Thomas, MG.

2000. High-resolution Y chromosome

haplotypes of Israeli and Palestinian Arabs

reveal geographic substructure and

substantial overlap with haplotypes of Jews.

Human Genetics 107: 630-641.

Nebel, A., Filon, D., Hohoff, C., Faerman,

M., Brinkmann, B., Oppenheim, A. 2001.

Haplogroup-specific deviation from the

stepwise mutation model at the

microsatellite loci DYS388 and DYS392.

European Journal of Human Genetics 9:22-26.

Nebel, A., Filon, D., Brinkman, B., Majumder,

P., Faerman, M., Oppenheim, A. 2001. The Y

chromosome pool of Jews as part of the

genetic landscape of the Middle East.

American Journal of Human Genetics

69(5):1095-112.

Nebel A, Landau-Tasseron E, Filon D,

Oppenheim A, Faerman M. 2002. Genetic

evidence for the expansion of Arabian tribes

into the Southern Levant and North

Africa. American Journal of Human Genetics

70(6):1594-6.

Nebel, A., Filon, D., Faerman, M., Soodyall,

H., Oppenhei, A. 2004. Y chromosome evidence

for a founder effect in Ashkenazi Jews.

European Journal of Human Genetics (in

press).

Health and Disease Studies in Past

Populations

Investigations of human skeletal remains

allow reconstruction of nutritional status

and general health from birth to death.

Physical anthropologists have developed many

techniques for assessing health conditions

and for analyzing their possible causes.

Methods used include measures of health

during childhood, such as stature, location

and severity of dental enamel defects,

cortical bone thickness and the presence or

absence of growth arrest lines. Differential

diagnosis of trauma or disease affecting the

skeleton include morphological,

roentgenological and histological

techniques, chemical and ancient DNA

analyses.

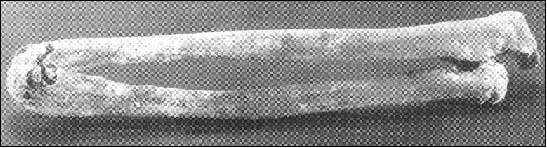

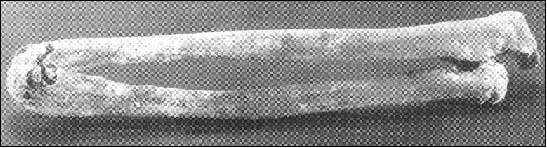

Hand amputation. A complete skeleton of an

adult male, aged 45 years was discovered in

one of the MB-II shaft tombs excavated in

the village located in the Refaim valley.

The right hand was missing and the right

radius and ulna foreshortened and fused

distally.

|

| Amputation of the hand. The

distal ends of the radius and ulna

are fused in this 45- year-old male

found in a shaft tomb in Jerusalem

dated to the Middle Bronze I Period

(~3800 B.P.), presumably following

amputation of the hand. Photograph

shows the right radius and ulna with

shortening and rounded fusion of the

distal ends (Bloom et al. 1995). |

No evidence of significant periosteal

reaction, cloacae or distruction was

observed. Radiography demonstrated firm bony

union of the distal shafts of the right

radius and ulna.

|

| Radiograph showing firm bony

union of the distal ends and absence

of infection. |

The amputation occurred in adult life as

evidenced by the full development and normal

cortical thickness. The appearances are thus

consistent with good healing, following

surgical amputation of a healthy hand or one

traumatically damaged, and is likely to have

occurred at least 1 year prior to death.

This case is the earliest example of limb

amputation originating from Israel (Bloom

et al. 1995).

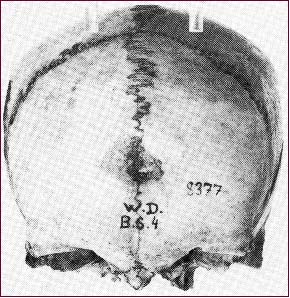

Skull trephination. During the excavations

at Arad a tomb cave dated to the Early

Bronze age period was discovered which

contained several secondary burials. The

cranial bones of one the individuals, a

young male aged 16-18 years, showed scars

from an old trephination. A large shallow

symmetric depression with shallow sloping

edges was observed on both parietal bones.

|

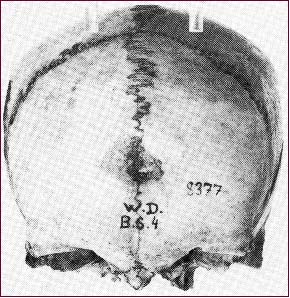

Trephination: Arad, upper view of

the cranial vault. Two symmetric

depressions, resulted from scraping

with a sharp object are seen on the

parietal bones of the skull of a

16-18 male individual from the Early

Bronze Age II period (~4000 B.P.)

(Smith 1990). |

The size and form of the lesion suggest that

this was a trephination carried out by

scraping. The well-healed lesions show that

the death was probably unrelated to the

operation and occurred at least one to two

years post-operation (Smith

1990).

The Goliath Injury. A healed depressed

fracture was found in a Samaritan male aged

about 35 years and dating from the 4th

century B.C. This fracture was located in

the center of the forehead and had a smooth

hemispheric shape.

|

Frontal view of a cranial vault of a

Samaritan male (2300 B.P.) aged +35

years showing a healed depressed

fracture in the center of the

forehead. It was possibly caused by

a round, smooth missile delivered

with considerable force (Bloom,

Smith 1992). |

A lateral radiograph of this depression

demonstrated it to be a well-healed

depressed fracture of the frontal bone with

no signs of associated osteomyelitis.

|

Roentgenogram of the fracture. |

The smooth concave appearance of the

depression suggests its causation by a round

smooth missile delivered with considerable

force. This injury may have been the result

of a slingshot wound similar to that of

Goliath who was felled by a stone from the

sling of the young David (Bloom

and Smith 1992).

Ancient DNA analysis is a new research

approach with many applications in fields

ranging from genetics through emerging

diseases to forensic medicine. Our

laboratory has pioneered this field in

Israel. The research has been mainly focused

on the genetics of past and present

populations of Israel, Middle East and

Europe with the main emphasis on population

origins, disease patterns and host-pathogen

relationships.

Anemia. The potential and reliability of DNA

analysis for the identification of human

remains were demonstrated by the study of a

recent bone sample, which represented a

documented case of sickle cell anemia (Faerman

et al. 2000). β-globin

gene sequences obtained from the specimen

revealed homozygosity for the sickle cell

mutation, proving the authenticity of the

retrieved DNA. Further investigation of

mitochondrial and Y chromosome DNA

polymorphic markers indicated that this

sample came from a male of maternal West

African (possibly Yoruban) and paternal

Bantu lineages. The medical record, which

became available after the DNA analyses had

been completed, revealed that it belonged to

a Jamaican black male. These findings are

consistent with this individual being a

descendent of Africans brought to Jamaica

during the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

It is commonly assumed that the endemic

disease load increased with the

establishment of large sedentary

settlements, but there is little direct

evidence of the pathogens involved. Several

hereditary diseases, primarily

hemoglobinopathies, are highly prevalent in

populations residing in regions that have

been infested by malaria.

β-thalassemia is

widespread in sub-tropical malarial regions,

the Mediterranean basin and the Middle East.

It has been suggested that the disease

provided genetic protection against malaria.

Claims for the occurrence of thalassemia in

prehistoric populations have been made on

the basis of skeletal pathology (porotic

hyperostosis). We reported on detecting a

known mutation in the β-globin

gene in the skeletal remains of a child with

severe porotic hyperostosis (Filon

et al., 1995). This study is the

first and so far the only direct proof that

porotic hyperostosis, observed in the

skeletal remains found in the Mediterranean

region, is a result of genetic anemia.

The shift to agriculture and animal

husbandry revolutionized the frequency and

number of contacts amongst people and

between them and animals. It is generally

assumed that, as TB probably occurred as an

endemic disease among animals, the first

human TB cases may have been contracted from

cattle, and Mycobacterium bovis, the agent

of cattle TB, was the most likely first

infecting organism.

Many clinical forms of tuberculosis leave no

specific traces on the human skeleton.

Infectious diseases can be traced through

identification of DNA of a specific pathogen

from human remains. We detected the presence

of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in skeletal

remains dated back to the 1 millennium A.D.

from North-Eastern Europe by amplifying a

part of a repetitive insertion element-like

sequence (IS 6110) (Faerman

et al., 1997). DNA of the bacillus

were identified both in pathological and

normal tissues (bones and teeth) of the same

individuals, and also in skeletal remains of

individuals without specific lesions. The

results suggested that a higher percentage

of the individuals might have been infected

than can be estimated from the incidence of

bone pathology. These findings open the

possibility of examining the actual

prevalence of tuberculosis in ancient

populations from collections in which

individuals are represented by single bones

or teeth.

|

|